- Home

- Jonathan Franklin

A Wild Idea

A Wild Idea Read online

Map

Dedication

Totinha—I adore you!

You’ve made these past

four years the best of our life.

Epigraphs

He was just not impeded by any kind of realities or practicalities—it was like, What do you want? Don’t limit your potential with a lack of imagination. If you don’t think big, it’s never going to happen. I don’t think he cared too much what other people thought. I don’t think he was trying to please anybody else. And “get out of my way, I’m going for this vision that I’ve created.” And that’s potent. It’s heady.

—QUINCEY TOMPKINS, oldest daughter of Doug Tompkins

He was fearless. He never turned his back on a difficult problem, a difficult conclusion, or an overwhelming challenge—an overhanging cliff on a climb, or a planet where loss of habitat and global warming were putting the future in danger. Doug never stopped, never slowed; he was the quintessential man of action—a force of nature, for nature.

—LITO TEJADA-FLORES, filmmaker and climber

At the summit, we got nailed by this huge ice storm, and Doug thought he knew the way down and started leading us. Suddenly he stopped. He froze. He was at the edge of a precipice a thousand feet down. He was completely wrong. Then I pulled a compass out—what I call a Boy Scout compass. We were 180 degrees off and Yvon Chouinard gets right up in my face and said, “Isn’t this great! Makes the whole trip worth it!” And I am thinking, What kind of maniacs am I with?

—TOM BROKAW, NBC television anchorman, author of The Greatest Generation

Doug learned fast; he felt like he was invincible because the normal amounts of risk didn’t apply to him. If you ever flew with Doug in his plane, you’d know what I mean. He took us on a flight over Patagonia, and it was all I could do to keep my stomach down. He would set it on one wing and spin around and around looking at something. He clearly had that quick-twitch, fighter-pilot stuff.

—DAVE SHORE, rafting guide

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Map

Dedication

Epigraphs

Author’s Note

Part I

1.The Rucksack Revolution

2.Conquistadors of the Useless

3.The Snow Cave

4.Plain Jane Goes Mainstream

5.Esprit de Corp

Part II

6.Where Is My North? Flying South

7.Earth First!

8.Pioneer Village

9.Stalking Tigers in Siberia

10.Two Exotic Birds in a Strange Land

11.Salmon Wars

Part III

12.The Land of Shining Waters

13.Pumalín Park

14.In the Heart of Patagonia

15.The River Killers

16.Operation Musashi

17.River Keepers

Part IV

18.Puppet Shows for Parrots

19.The Route of Parks

20.Ambushed in Patagonia

21.Year 1 A.D.—After Doug

22.Islands in the Storm

Author’s Note

List of Interviews

Suggested Reading

Acknowledgments

Photo Section

About the Author

Also by Jonathan Franklin

Copyright

About the Publisher

Author’s Note

I lived many years in awe of Doug Tompkins. He’d done the impossible—climbed to the heights of corporate America and then cashed in his chips, taken his millions, and fought for nature. I admired his fight for native forests, grasslands, rivers, and wetlands. I visited many of the remarkable national parks he created in South America. When my Uruguayan friend Rafa called to tell me that Doug had died in a kayak accident in December 2015, I immediately felt like an idiot. How had I not spent more time with this genius in my midst? How had I only interviewed him a half-dozen times in his last ten years?

As I set off to write this book I sought to capture the essence of his remarkable life, and I felt qualified for the challenge. My passion for the great outdoors set in early—bouldering in New Hampshire and swamp exploring in Massachusetts. Like Doug, I was a downhill ski racer and loved testing the limits of speed and control. Doug took his passions to San Francisco, then in 1989 flew down to southern Chile. I too followed a similar path, traveling from San Francisco in 1989 to explore southern Chile by mountain bike. Like Doug, I have spent half my life in the United States and half in South America.

When I first queried Kris Tompkins for permission to write a book about her late husband Doug, I knew I didn’t have to ask. In fact, she confirmed that when she told me, “You don’t need my okay; you can just go and write it.” Kris was right, but that was never the book I wanted to create. I was interested in the inside story of a remarkable man. I interviewed Doug enough during my nineteen years reporting for The Guardian to know his close friends were protective and almost tribal in their secrecy. Then Kris said no. They couldn’t help me on the book. Eight months later, I asked Kris again for her permission and collaboration. Again I was told no. Kris was too busy.

I tried again. If she didn’t have the time, could she at least give her blessing? Could we agree to walk separately down the same path? The biography would not be authorized but collaborative. We could share notes, impressions, and stories in the wake of her husband’s shocking death. Here we found a common ground that, after two years, blossomed into a collaboration beyond my imagination and eventually hours of face-to-face conversations with Kris.

Kris received my calls, read my emails, gave long interviews in Valle Chacabuco and Pumalín Park in Chile, met with me in Rincon del Socorro in Argentina, and, as I was finishing the book, made time for video calls from her home in California. She shared Doug’s love notes, private emails, personal photo collection, and stories of their life together. She shared his passion for conservation and was generous in sharing his life with me.

For nearly four years, I explored the world of Doug Tompkins. At his park in Patagonia I took an afternoon walk through Chacabuco Valley, aware that wild pumas roamed nearby. Instead of scary it was invigorating; a sense of longing awoke inside me—as if I needed a reminder that humans too are part of the food chain.

While visiting the national parks Doug had established in Argentina, I could hear but not see a family of howler monkeys high in the trees. My seven-year-old daughter, Akira, mimicked the call and the howlers descended, curious about this strange little monkey—roughly their size. For minutes they stared eye to eye at one another, calling back and forth. Akira continued mimicking monkey talk, and the howlers chattered among themselves excitedly as they discussed the meaning of this new voice in the woods. Everyone present felt the connection, the communicating, the communion. I had brought my children on the reporting trip hoping that in the wild spots that Doug Tompkins saved perhaps some wild would rub off. Might they return home themselves rewilded? Akira’s encounter with the howlers made it all seem possible.

This book is my journey into one man’s love affair with the wild. The wild mountains, forests, and rivers. Doug Tompkins was also wild. Competitive, hyperactive, and as flawed as his friend and neighbor Steve Jobs, with whom he argued at parties. Tompkins was an environmentalist who drove a red Ferrari. A multimillionaire who preferred to sleep on a friend’s couch. He was a stickler for details, yet he hardly noticed his two daughters right before his eyes. Hard-nosed, arrogant, and argumentative, he despised compromise.

The world for Doug Tompkins was black and green: you were either a scourge or a seedling. He never seemed to worry what others thought. When the media savaged him, Tompkins laughed. He told Thomas Kimber, a young entrepreneur wh

o was his neighbor, “It doesn’t matter; in fifty years they will be building statues of me.”

Like the way he drove cars and paddled kayaks, Doug Tompkins rarely looked back. Yet, for all his faults, I found myself transfixed by this rock climber who at the age of forty-nine and atop the peak of capitalism took a deep look around and admitted to himself, “I’ve climbed the wrong mountain.”

To understand this complex man, I conducted roughly 165 interviews ranging from his seventh-grade classmate Stone Ermentrout to his lifelong friend Yvon Chouinard. I sat for interviews with Susie, his first wife; both his daughters; and dozens of employees who loved him plus a half dozen who loathed him. Notably, by the time of his death, Tompkins had converted many adversaries into allies. Critics who thought he was exaggerating the demise of planet Earth—people who wondered what he meant when he said that extinction was the “mother of all crisis”—began to see that he had offered them not a doomsday scenario but a glimpse of the future.

The planet has never needed defenders more than now. Wherever we look, environmental news is bad news. Forest fires. Global warming. Extinction. It’s a litany of loss and destruction that Doug Tompkins fought so hard to slow. He liked to quote his mentor Arne Naess and say he was “a pessimist for the twenty-first century and an optimist for the twenty-second century.” Despite his pessimism about human behavior, Tompkins maintained faith that the Earth could recover.

During the COVID lockdowns it became evident to many urban and suburban residents that the animals are still out there. Pumas have visited silent urban centers, turtles have hatched on untouristed beaches, and dolphins have explored suddenly quiet coastal waterways for the first time in decades. Given a respite, a chance to breathe, nature is resilient. But change requires action. Tompkins quoted the naturalist author Edward Abbey, who mocked the idea that economic growth was a measure of economic health. “Growth for growth’s sake,” Abbey once cracked, “is the philosophy of the cancer cell.”

For Tompkins, the key to environmental health was not growth but stability. He recognized that on a finite planet there is a deep need to give as much as we take and that before we die, we must leave the world a little bit better.

As I wrote about the life of Doug Tompkins, I attempted to describe this book in a narrative that my eleven-year-old daughter, Zoe, could understand. I sought to help her, even at that young age, understand the concept of a legacy with dignity. I told Zoe that Doug Tompkins—whom she’d heard quite a bit about during her dad’s four-year journey—felt that a most noble goal in life was to leave the planet “a little bit better.” She smiled, nodded, and then asked the kind of question so natural to a child and so poignant for an adult: “Why only a little bit better?”

Jonathan Franklin

Punta de Lobos, Chile

Part I

Chapter 1

The Rucksack Revolution

Doug is the kind of person you could throw out in a desert naked with a stick, and within a couple of weeks he’d have an empire. I think he’s the most street-savvy human being I’ve ever known. Wherever he landed, whatever situation he was in, he worked out all the street angles way faster than anyone else. It was not always according to the book, or legal, but it worked.

—DICK DORWORTH, the world’s fastest skier in the 1960s, a frequent travel companion of Doug Tompkins’s

Doug Tompkins paced the San Francisco sidewalk, hawking downhill skis to beatniks and groggy sailors. Fast on his feet and quick with a retort, the twenty-two-year-old thrived on the weave and bob of the street salesman. The charismatic high school dropout badgered customers to peruse his eclectic collection of custom-forged climbing pitons and fishermen’s sweaters from Scotland that he promised were resistant to any winds. Like a fencing champion, he parried back and forth with the pedestrians outside his store, trying to sell, sell, sell. “Need a sleeping bag? Wool pants? An ice ax?” he crowed to onlookers ambling past his quaint storefront in North Beach.

It was 1965. The store had been open barely a year and cash was tight at the tiny startup. Doug’s entire $5,000 budget was gone—spent on a storewide overhaul and a meager pile of equipment. Salaries were reduced by convincing climbing buddies to help with the street hustle. Compensation included a front-row seat at the hottest street scene in all of San Francisco, plus free beer.

Tompkins loved to dress up. Like a circus performer, he often switched outfits, and whether it was with his black top hat or his furry, ankle-length jacket, he appeared stylish yet brash. So too his shop. When customers asked why he named his retail outlet “The North Face,” Tompkins answered with the brazen air of a man who loved bombing down a mountainside on wooden skis and reaching speeds approaching ninety miles an hour. “The south face is the most often climbed, the snow is softer, and the sunlight makes it warmer,” he said with a sigh. “I prefer the more difficult side. The hard, icy face. The North Face is a more difficult challenge. I take that route in life.”

Although it was decades away from being a globally recognized clothing company, the original store called The North Face, created by Doug Tompkins as a twenty-one-year-old, was just the first of his three mighty brands that he would turn into world-renowned enterprises over the course of his life. Disruption was his game and, according to his best friend, Yvon Chouinard, founder of Patagonia clothing company, Doug liked nothing better than breaking the rules. “If you want to understand the entrepreneur, study the juvenile delinquent. The delinquent is saying with his actions—This sucks! I’m going to do my own thing! That was Doug. That’s why he dropped out of school, because, like a lot of kids, he couldn’t tolerate just sitting at a desk and being told what to do, and he just had too much energy for that and too many ideas floating around in his head.”

In front of the plate glass display windows featuring an oversized Bob Dylan poster, Tompkins and Chouinard harangued pedestrians walking through the North Beach neighborhood—some on their way to Chinatown, others coming up the hill from the docks. Yvon plopped Quincey (Doug’s infant daughter) atop his shoulders as a conversation starter to lure customers in. When Quincey tired, he lay her down for a nap in the display window. The cute baby, naked as the day she was born, sleeping atop a pile of fluffy reindeer-skin rugs became a hit in the growing lore of the community.

Besides selling newfangled skis and cutting-edge mountaineering equipment and clothing, Doug’s store was becoming known as the place where “the baby sleeps on the reindeer rugs,” and inside the shop there were often raucous gatherings, intense debate, and an eclectic crowd feeding off what was quickly becoming “the North Face scene.”

Tompkins and Chouinard bickered and bantered like a comedy team as they pestered pedestrians. They kept up a running commentary on the ridiculous nature of their proposition. Who sold 120-foot, spun-nylon Austrian climbing ropes to half-drunk sailors looking to party? To their right was Big Al’s Saloon. To their left, dancers enticed businessmen into The Condor Club—a novel strip bar where in the evening, when the music cranked up and a white grand piano was lowered down from the ceiling with the busty Carol Doda coyly splayed on top, the floorboards at The North Face reverberated with tremors, like a small earthquake. Between shows, the strippers hung out with the climbers. Tribe to tribe they shared the thrill of breaking traditions and routines. “He looked totally out of place in that shop. The strip-show barkers outside their bars, a horde of low-lifers cruising Broadway,” said Chris Jones, a fellow climber who met Doug when he purchased downhill skis. “But he was always overflowing with energy.”

Boxed between dance revues and a string of sailor bars, The North Face store was center stage for the North Beach neighborhood’s explosive cultural upheaval. Across the street, the poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti ran City Lights bookstore, and provoked the nation’s leading moralists by publishing genre-breaking poetry and fiction. Allen Ginsberg’s poem “Howl” incensed the censors, who frothed at its celebratory references to illicit drugs and roaringly good sex. The uproar, of cou

rse, just made “Howl” that much more delicious for those with an appetite for rebellion.

As the carnage from the Vietnam War cleaved apart the national psyche, Doug was at street level taking it all in. “Drugs were just one part of a whole cultural, social circle at that time—drugs, music, permissive sex,” Tompkins later wrote. “It was a whole change of value systems going on then and a tremendous experimentation. Of course it was a very broad swing of the social pendulum. A new morality was being formulated. And I was right in the eye of the social revolution.”

An Italian immigrant neighborhood in the ’50s, North Beach in the ’60s was not as counterculture as Haight-Ashbury several miles to the west. Unlike “The Haight,” with its flood of youth who were seeking refugee status from mainstream America, North Beach was more like the staid ’50s than the revolutionary ’60s. But change was in the air, and in North Beach it took the form of tourists off the beaten track and passing revolutionary poets. Across the Bay, the Berkeley Free Speech movement at University of California’s Sproul Hall in Berkeley and Mario Savio’s passionate call on that campus to “put your body upon the gears” lit a fire on college campuses nationwide. In Oakland, the Black Panther Party fought for the cause of black liberation. Across the nation, J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI agents worked overtime to sabotage, squelch, and illegally upend the incipient uprisings.

At street level in North Beach, Doug and Yvon saw it all. They faced a daily ebb and flow of beatniks, tourists, and drunks. They loved the buzz. Doug’s wife, Susie Russell, added her own touch. She bought bikinis in France and then hawked them to her posh friends.

When they needed a rest from the hustle, Tompkins and Chouinard walked to the back of the street-level store and descended a staircase with missing planks, past a wall of exposed electrical wiring. In the basement they grabbed a snack and rested. The dirt-floored room was cool and dank. It was lit by a naked bulb and built into the side of the hill with an uneven floor that made the entire basement feel crooked, even when they didn’t smoke a joint.

A Wild Idea

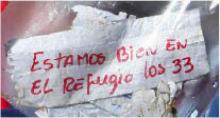

A Wild Idea 33 Men

33 Men